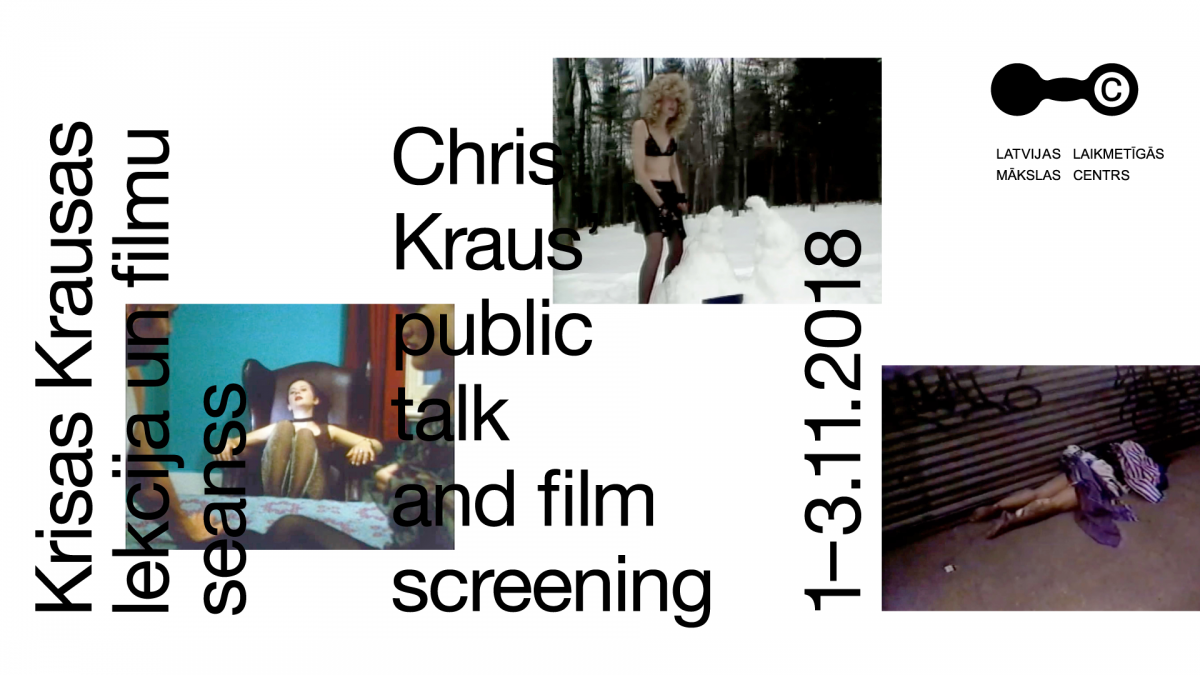

We cordially invite you to the What I couldn't write: Chris Kraus' Films from 1982 – 1995 on November 2 and November 3 at 6 PM at the art-house movie theatre Kino Bize, Elizabetes iela 37-2. We also remind you that on November 1 at 6 PM at the Art Academy of Latvia (New Building) Chris Kraus will give a talk on her new book Social Practices.

November 2:

Sadness at Leaving, 1992, 26 min 54 sec

Gravity and Grace, 1995, 89 min

November 3:

In Order to Pass, 1982, 26 min 54 sec

Terrorists in Love, 1983, 5 min 20 sec

The Golden Bowl or Repression, 1984-88, 12 min 23 sec

Foolproof Illusion, 1986, 17 min 41 sec

Voyage to Rodez, 1986 , 13 min 58 sec

How to Shoot a Crime, 1987 , 28 min 50 sec

Traveling at Night, 1990 , 11 min 54 sec

Kraus uses failure as a narrative starting point, then dramatizes it. To focus intently on the quality of the individual films, or the fact that they have been long-overlooked by curators and critics, would be to risk missing this crucial success of the exhibition. By creating a show of failed works about failure, Kraus creates a space to challenge the success-failure binary and examine her own subjectivity over her career.

To do so requires a certain decreation of self, which is perhaps the most compelling component of In Order to Pass. On Simone Weil, who embodied a philosophy of self-denial, Kraus wrote, “She wants to lose herself in order to be larger than herself. A rhapsody of longing overtakes her. She wants to really see. Therefore, she’s a masochist.” This notion of the desire to see as a form of masochism is potent throughout the exhibition, because to Kraus, to see the world often means to find ugly, unpleasant realities like failure.

The films largely feature wounded protagonists resigned to disgrace. In How to Shoot a Crime (1987), filmed with her then-husband Sylvere Lotringer, Kraus visits gruesome homicide scenes. In Foolproof Illusion (1986) Kraus builds a snowman in her underwear, complaining about a violent husband and reading the work of Antonin Artaud, the French playwright known for developing the Theatre of Cruelty. In Traveling at Night (1990) she joins a class of schoolchildren to learn about the history of the Underground Railroad. In Terrorists in Love (1983) a woman reads a manifesto in a bar: “We are minor members of the Paris Semio-Kinetic Post-Surrealist School, North American branch,” satirizing the art-theory world in which Kraus is active. The films are strongest when they exhibit Kraus’ trademark sardonic self-awareness.

Kraus describes the impulse to make the films as “A terrible megalomania, an insistence on being present – even when one has no personal presence – through one’s double, the film… Much as I loathe the idea of a feminine ecriture, I have to admit that the impulse to do this seems very female.”

Angry woman, artist, writer: Kraus’ acts of identity — the one who creates in response to patriarchal forces, the one who then writes about what she created — all relate to a more fundamental action of performative gesture. Above all, Kraus encourages us to read theory, including her own, as this kind of gesture as opposed to sermonic truth. To read her books or see her films is to be challenged to reject an antiseptic, clinically evaluative way of looking at art in favor of a more fluid, embodied criticism. The result with In Order to Pass is a robust interaction between the body of work and the artist that produced it.

Source: Emily Wells, “Chris Kraus’ In Ordert To Pass: Films from 1982–1995 at Chateau Shatto”. Artillery, May 31, 2018.

https://artillerymag.com/chris-kraus-in-order-to-pass-films-from-1982-1995-at-chateau-shatto/