Photo: Andrejs Strokins

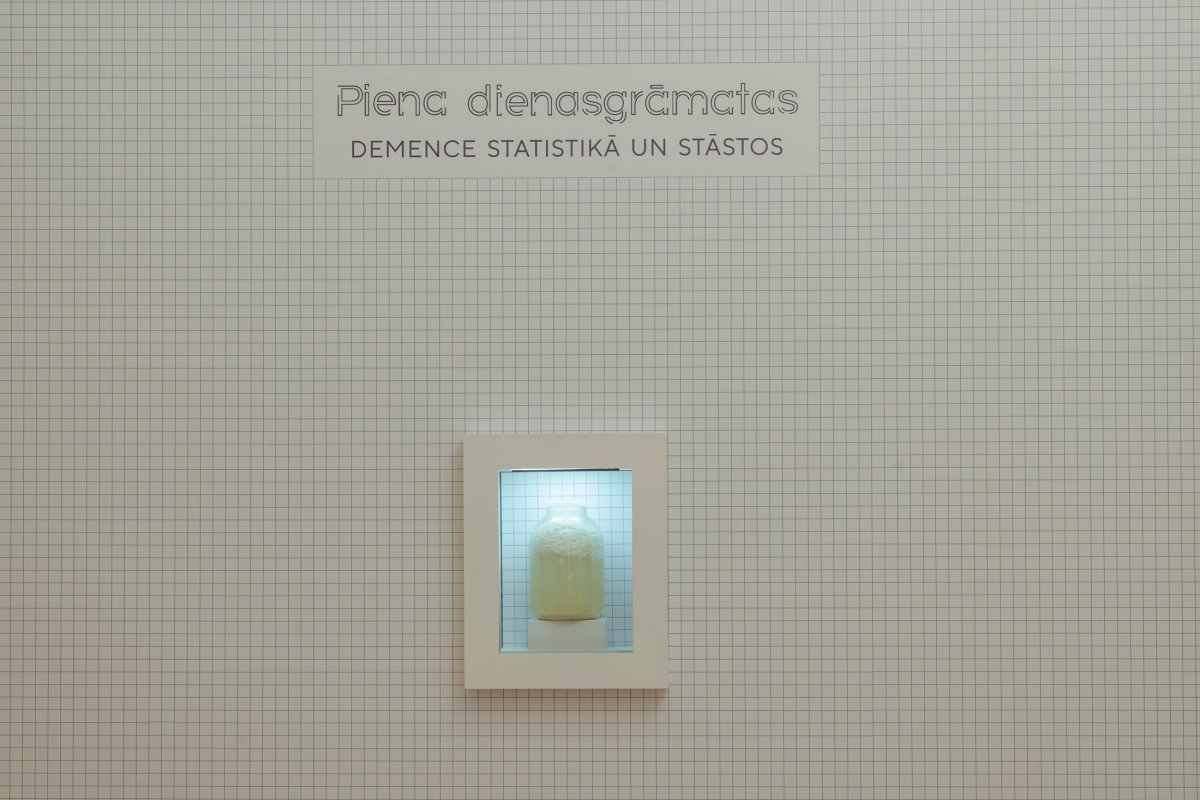

Until the end of the next week, June 5, we invite you to visit the exhibition "Dairy Diaries" by new media artist Anna Priedola, which through different media and forms tells the story of dementia and the experience of dementia.

Here you can read four stories from the exhibition - diaries of people witnessing dementia in their loved ones - which through four different examples of dementia of a husband, grandfather, father and mother-in-law reveal the everyday life and difficulties of people with dementia and those taking care of them living in Latvia.

Find out more about the exhibition here:

https://lcca.lv/en/exhibitions/exhibition-Dairy-Diaries-on-display-at-the-Museum-of-the-History-of-Medicine/#izstade

Diaries of witnessing dementia

The husband

1.

It’s Monday. It’s late February. The weather is exceedingly foul, to the extent that, as they say, a master wouldn’t let his dog out, with rain and snow mixed. We are at home, the two of us, me and my husband.

I asked him: “What day is today?”

He replied: “It’s Friday.”

I then asked: “How come? It was Sunday yesterday, when our daughter called. She usually calls on Sundays. Don’t you recall?”

He replied: “Indeed! That means it must be Monday.”

I asked him: “How are you feeling?”

My husband said: “I don’t really want anything. I only want peace.”

“Okay,” I told him, “then let’s start making dinner and watch the news after.”

Yes… a lot has changed since that time. Six months ago we arranged everything we need for our new relationship at the SAC social services center. I am now called an assistant. My husband is now a client of mine. We have a contract. I have entered an employment relationship. Each month I have to write a report on services provided, while my husband signs it as the recipient of the service.

This new relationship started a couple of years ago. Back then, I didn’t really understand that a disease was starting to run its course, followed by a diagnosis of vascular dementia. I knew virtually nothing about it. Only later I slowly started collecting information. We live together, the two of us. Our children are grown and long since have their own lives. We talk on the phone and meet regularly (if they have, of course, arrived in Latvia). The children are aware of the issue of dementia and they understand and make sense of it well, whereas other relatives and friends have but a superficial notion of it.

I have come to terms with the fact that it’s a long process. It is irreversible and deteriorates continuously. But let’s save this for later. For now let’s watch television, and the day will draw to a close.

2.

It’s overcast today, with wet snow. At least it’s not raining! It is a strange day. Russia has invaded Ukraine. There’s perpetual tension, not only in the great Outside World, but our own little world as well. We are invited to a presentation today. A company is advertising its newest products. I think to myself – how will it turn out? Will we be able to attend without any incidents? Thankfully, it takes place close to home. Not more than ten minutes away on foot. In the morning, I thought whether it’s best to clue in my husband that we’re going, or not. I made up my mind that it was useless to tell him in advance. Either way, he would have forgotten it momentarily.

Today it’s my client’s turn to ask me what day it is. Is it Monday? “No, it’s Tuesday already! Just use the tear-off calendar. I’ll place a bookmark inside it,” I told him.

As recently as last year, my husband would tear calendar pages off and correct the date on his own. He no longer does, and I have to come up with ways of reminding him to do it.

As is usual, life introduces its own alterations in our daily lives. I was on personal business in the morning and couldn’t make it back home. The event was to start in an hour. I called my husband. It was late in the afternoon but I didn’t know whether my client would have woken up by then. The call finally got through. He had just gotten up. Thankfully. I told him to eat something quickly and that afterwards we have to get ready to go outside. I didn’t tell him where we’re going, as he would have forgotten either way. He called me after a little while. We agreed upon meeting at the gate by the house. It came to pass, we met up and got going. Thankfully, we had enough time, but in the past we would have arrived much faster. My husband has a much slower gait now. It’s incomparable to how it was before. He used to walk like a racewalker, with a springy and light step. But by now he moves about stooping and shuffling his feet.

On the way there, I couldn’t restrain myself for a minute and burst out when my client kept asking, once every few minutes, Where are we going? I retorted: “How many times must I repeat myself? Am I a damn answering machine?”

Thank god, we’ve finally arrived. There are only the two of us, another visitor and the presenter in the room. It all goes well. We feel at home in the office space, and my husband doesn’t do anything inadequate. After a couple of hours it comes to a smooth conclusion and we return home. We’ve completed today’s program, having talked for close to three hours and learned something new. And taking a walk in the fresh air is wonderful in itself! Enough for today.

3.

Wednesday. It’s clear outside. It is perhaps a moment for reflection when great changes are imminent. A day of reflection in world politics as well. The great powers have recovered from the shock caused by Russia’s aggression; they’ve started analyzing the events and working out their own tactics and strategies.

It is similar at home. I started working at a new job and I’m considering what tactics and strategies I should employ now in our assistant-client relations. Thank god, work starts early in the morning and I get to return home early, in the afternoon. My husband usually sleeps in, always putting in at least a solid thirteen hours. I asked my general practitioner whether it’s related to the pills he takes regularly. She replied in the negative, and so I still don’t know the cause behind his prolonged periods of rest.

I got home a bit late today and thought that my husband would have eaten and would be sitting at the table. Finding him still in bed therefore surprised me.

I asked him: “Are you still sleeping?”

He said he had already broken his fast.

“What did you eat then?”

“I don’t recall. I must have eaten something,” he answered.

I checked it, and the food I had left him for breakfast had indeed gone. He had also taken the pills.

“How come you are sleeping right now?” I asked him.

He said he had simply laid down for a while.

“Don’t you want to do something, or maybe go outside for a walk?”

“No. Peace and quiet is all I need.”

I am torn apart by conflicting thoughts and feelings. On the one hand, I have a peace of mind of sorts when my client is sleeping and nothing out of the ordinary, nothing extreme has happened. Unlike it did yesterday, for example, when my husband had closed the wardrobe door without noticing that our cat was sleeping inside. Thankfully, I started looking for her in the morning and found her. It is good to have a kitty of our own to be together with him when I’m away. She’s a living being after all, and a member of our family. On the other hand, the actions of my husband are sometimes unpredictable, and our supposedly peaceful way of life is interrupted by incomprehensible and unforeseeable turns. And, most importantly, for how long can a human being lie flat like this?! After all, as living beings, people need movement, activities and fresh air.

I asked him if he knew what day it was. He said it was Thursday, maybe Friday. And thus he still remains clueless as to what day it is today. I am also at fault as I didn’t move the bookmark on the calendar. That’s our life. For me, it’s almost uninterrupted suspense with fleeting moments of respite.

4.

February 24. It’s a sunny day here. But for people in Ukraine and Europe time has become thrown off balance with the beginning of the war. I have sometimes opined that people in power should be evaluated for soundness of mind. Others objected to this, saying that it would be non-democratic and unethical, that this would amount to a human rights violation… Nevertheless, down to the present day, human history has borne witness to power-intoxicated aggressors subjecting entire nations to immense destruction and suffering. And many of them have been unhinged, and particularly often mentally impaired.

Today we have heard a lot about the Russian president not being of sound mind. He has sparked a chain of destruction that has led to people dying and entire regions being razed. I find my client and the people similar to him to be more adequate.

Nevertheless, we found something to be happy about today. Municipal social services wired us the monthly sum for my services in the capacity of assistant to the client. The money isn’t much, not more than 39 euros. This is the pay for the fifteen hours we’ve spent together. Of course, this, too, misses the mark! I had to be with him day and night, for twenty-four hours. But this is what the committee decided based on the medical data over the state of the client’s health. They’ve come to a decision on conferring the appropriate disability status.

The central government and municipalities have made submitting reports a lot easier. Indeed, I only have to fill in a single page listing hours worked. Further corroboration with seals and signatures is no longer necessary. It can be submitted to social services both in paper form and digitally. But I must say that there’s a ‘take’ for this ‘give’. Clients were shocked about the steep reduction in wages in the payment system. The two of us were likewise not happy. Nevertheless, seeing as we established these relations only last fall, we didn’t count on financial support much. We endured this and came to terms with it.

Nevertheless neither I, nor my client can come to terms with what has happened in world politics today. We realized that we would keep following reports in the future and information about the ways in which we can help. Daily life has definitely become more stressful, and no one knows how it will turn out. We have to be prepared for anything. But, for now, may the Almighty protect us.

5.

It’s Friday, we have changeable weather and the European political reality is now different from before. Ukraine is going through its second day of the war. By now there are fatalities and great destruction. International institutions are working on documents related to limiting Russia’s aggression. Meanwhile Latvia has collected almost a million euros in financial aid. The first war refugees from Ukraine are expected to arrive today, and aid plans are to be worked out to help this country. In the evening, a concert will be organized across the street from the Russian Embassy. And one could even say that the issue of Covid has, as it were, receded into the background.

As I return home from work, my client welcomes me wearing his socks. He says he has laid down to rest for a little while. Thank god, he has eaten breakfast and taken his medicine. He does very little on his own accord, but when he does it’s often unpredictable and the result must always be double-checked. At times, the outcome may turn out quite shocking.

I keep reminding myself that his short-term memory lasts for only a few minutes. But there are times I cannot take it. I shatter into pieces, emotionally. Of course I regret it at that very moment. One should always be mindful of what psychologists advise in working with clients who have a such-like diagnosis. I keep reminding myself to remain calm. Count to ten and explain, calmly, what needs to be done. Don’t criticize. Be mindful of your tone. But nevertheless I slip up, and this results in unnecessary stress and an emotionally charged atmosphere.

Actually, one should be very precise in one’s wording upon explaining what needs to be done. One must avoid giving too much information. It’s best to repeat only one single thing but do it very clearly and in great detail. If one doesn’t follow this, the result is sometimes such that you don’t know if you should laugh or cry. Like today. It was something similar to Bulgakov’s The Notes of a Young Doctor where a doctor told a country woman to use mustard plasters for her back pain. After a while she arrived to see him and complained that these were of no use. The doctor asked her, How did you use the plasters? On your back? The woman replied affirmatively and showed her how she had gone about it. The doctor was shocked upon seeing plasters attached on the back side of her thick quilted jacket.

Well, today I had a similar situation after I asked if he could take out parsley from the bags and tie them up to be dried. As a result, it was an interesting sight to see several bundles of parsley, wrapped in plastic bags, being tied to shoelaces. But what is there to be done? It’s my fault, I should learn from my mistakes. But for now I should listen to the concert. I could say that we both feel as if during the 1991 Barricades.

6.

Saturday. It’s sunny outside. On the news, they say that military specialists consider the war in Ukraine to have entered a slowed-down or stagnant phase. Locals are asked to remove road signs and direction signs in order to mislead the invaders.

I think that me and my husband have also entered a phase of stagnation or, as it were, a conservative phase. Having direction is important in life. It is important both physically and mentally. This includes having direction as concerns ideology, good and evil, war and peace.

A couple of years ago I visited an acquaintance. I was surprised to see reminders in the bathroom, saying:

“LOWER THE SEAT!”

“FLUSH THE WATER!”

I thought to myself that this was quite strange! Why would signs like these be necessary?

Only later did I learn that the husband of this acquaintance was affected by dementia. I am now considering making such reminders of my own. It is of no use repeating, day after day, what clothing should be worn and at what time; what each spoon or cooking pot is for; when ventilation should be turned on. It’s better to write reminders and then wait if it has any effect.

This may be something peculiar to us, but we have great trouble with personal hygiene, or changing into clean clothes and washing up. It is always accompanied by scandals and hateful excesses. What scares me the most is his hateful aggression. At such moments I am overcome not only by anger but also panic and a feeling of helplessness. I don’t know what to do. The suggestions that the GP gave him about hygiene are of no help. He usually expresses his aggression by slamming the door and bursting out cursing.

How will this turn out? I don’t know… It is clear that my client’s sense of direction is deteriorating. I no longer allow him to take the trash to the recycling bins in the yard. I know that if I don’t keep close watch it will not be done correctly either way. Even though just a year ago he was still able to go to the park, buy products on the shopping list, and wait for me to come back home from work at my stop, I no longer trust my client. I realized I no longer could after several times when, after being sent to get something on a route he supposedly knew, he had gone somewhere else, not where I had asked him to go. He couldn’t recall if he had been to the place at all… I’d no longer allow him to take the recognizable, straight path to the dentist’s, not to speak of using public transportation to go somewhere, even though he has a note in his pocket with all the information about his person! I asked him, Why didn’t you do what I had told you to do? You had it all written down. He replied: “I got confused. It all became mixed up in my head.” Unpredictable behavior is another thing that scares me. I can no longer find folders of important documents on the desk. When I asked where they had gone, he told me he didn’t remember.

Well? It’s your own fault. You should have given more thought to placing, hiding or moving these things. In the future, I have to think about what I should do with the matches, the gas and the water taps.

7.

It’s Sunday. The weather is fair, and I could say that today’s reflections center around three basic notions, that of time, that of peace and that of humanity.

Time is marching ahead, and we don’t know the way the events in Ukraine, Europe and the World will turn out. We can only hope and wait for peace, a peace that is also vitally for meditating upon what turns we can expect in the future. And finally humanity, which everyone needs acutely.

I don’t know the way in which time will affect my assistant-client relations. I am an optimistic and positive person by nature. But I understand, as a realist would, that my husband’s health will deteriorate irreversibly in time. I think that we are still doing quite well at the moment. What I don’t know, however, is for how long I will be able to take this, both physically and mentally. Will I not end up on the verge of exhaustion and burnout? I need a period of peace and quiet in order to recover from the perpetual strain I’m under. I long, and extremely so, for normal family relations!

It is good that clients have rehabilitation programs. But don’t assistants need these as well?

And finally – humanity. How can we ensure a dignified life for our clients? I try doing what I can. My husband is still reading his favorite adventure novels, history magazines. He still watches TV and listens to his favorite musical pieces. Last summer we even went to a concert by Raimonds Pauls! Nevertheless, it sometimes seems that the decisions which state institutions make about our clients consist, to a greater extent, of rhetorical flourishes rather than true concern over ensuring a dignified life for them. Of course, something is being done, but, it seems, in a sporadic rather than holistic manner. As of now, we still lag behind other countries, and this is true both as concerns educating the public and helping clients recover. The first swallow we have here is a cafe for people affected by dementia.

Over the past couple years since my husband developed this disease I have learned a lot and gotten some education. It has helped me to test the humanity inside me, the limit of my compassion, understanding and restraint towards others. It is important to educate the younger generation and the rest of the public about integrating such people in our society.

Do you know what has been the most difficult thing of all? For me, it has been observing, day after day, how one of the people closest to me is slowly turning into someone alien to me, someone only distantly similar to his former self. I have greatly benefited from talking and sharing my pain with the years-long acquaintance whose husband also recently developed this disease. I am thankful to everyone who has supported us.

And in the end I would like to paraphrase Gunārs Astra to say something about these events: “I believe that this era will come to an end like a bad dream would.” And in my own words – an evil regime that is lacking in everything human can never prevail. Let’s be united in our humanity! Peace be with you!

The grandfather

The first sign that grandfather (all of us usually called him grandpa) was developing dementia was him starting forgetting where his stuff, his instruments were. We asked him, “Where do you have this? Where do you keep that?” He replied, “I don’t know. I must have put it away somewhere.” But only later on would we understand what it meant.

Sometime, in the final months of a certain year, we celebrated grandfather’s birthday. I had recently given birth, but grandpa never understood that it was his great-granddaughter. He joked around and played with my cousin, who was three years older than she was. He lived to see his great-grandchildren, but also, in a sense, he did not. He saw them but he couldn’t grasp the connection. Sometimes, without anything related happening, grandpa would drift away into his memories of war. He had experienced the Courland Pocket during the war. The hunger. He suffered from panic attacks which he likely developed after a burst of machine-gun fire from the air hit the ground beside him. Other than that, physically I mean, he was in impeccable health. He had always observed the golden mean both as concerns food and drink. He spent a lot of time outdoors. During the birthday party, however, grandpa would drink one glass after another. Dementia made him forget he had just emptied one. His wife was very worried about this and sometimes prevented him from topping up.

The following year, at about the same time, we celebrated the birthday of my daughter in my parents’ house. Then, the old folks could still arrive on their own, with grandpa at the wheel and his wife, in the passenger seat, telling him the directions. My uncle laughed, saying that one of them is clueless as to where they have to go, while the other can’t see the road right any more. But for some time the two of them would deal with their illnesses together, like a single whole. After the birthday party grandfather’s wife wrote to me, saying: “Grandpa failed to understand why we were visiting.” She had a great-granddaughter of the same age as my daughter, and both of them made her happy. Happy for two, because grandpa could no longer appreciate his kinship.

We celebrated grandpa’s 80th birthday in a larger space, outside home. What beautiful girls have arrived, he said. He asked me to dance. I must admit he remembered the dance moves better than I did. I think I had last danced ballroom dances in primary school, where they were included in the mandatory PE lessons. I danced with him as I would with a man I don’t know. I had to create a new relationship with this man, and this made me more of an adult than the birth of my child had.

A year later, grandfather’s wife wrote to me saying that he had recently stepped out of the car and failed to understand where he was. Now his driving had come to a stop as well. My uncle had read somewhere that such people should be allowed to drive as long as they are able to. “I don’t know if it’s true, but I really noticed that after he stopped driving he became worse much faster,” he said. “There were some incidents, of course. One time dad had disappeared somewhere with his car. He dropped his wife off at the store and then went to a different city. His wife and her neighbors went looking for him and found him driving sluggishly somewhere.” He would escape all the time. One time he had left his car by the store and gone off on foot, looking for his wife who had supposedly disappeared. He accepted his wife. If he saw him, it was alright. But his wife went away first. She died from cancer in December, while grandpa died months later, in February.

I received the final texts from my grandfather’s wife in summer 2016:

Grandpa is doing worse and worse. He is losing interest in life, and strange habits show up. He knows my name but not who I am… We were taken to a neurologist at the Stradiņš Hospital. It’s the last resort. They gave us pills which cost €15 a month. If these don’t help, the very last option costs €100 a month. These can only slow the process down, not make him better.

Sometimes, it seems to me that I, too, am becoming strange… My infrequent visits to Liepāja and Rīga keep me afloat, help me restart. Meeting my great-granddaughter helps a lot. That happens rarely. I only see what they do on social media.

During the time that my grandfather’s wife was in the hospital, his son took care of him. He worked in the city throughout the day and went to his father’s distant village in the evening.

The father

I first understood that it has all been lost, irrevocably, upon taking father home from a reunion. We stopped at a cafe to eat. I seated him at a table and went to make an order. Upon returning, I couldn’t make out who it was he was talking to. It turned out he was talking with his reflection in the window. He told me: “Look! Someone has come to talk to me.” Later on, at home, he looked into the mirror and started discussing things. I realized back then that this is final and will never improve. A child grows into a full-fledged person only when they start recognizing and becoming aware of themselves. Prior to this, they see their hands in the manner of a cat playing with its own tail. Here it was the other way around, with an adult growing into a baby. But I think that on his last day my father recognized me. He could speak no longer but he looked me in the eye, and I could see he understood.

When dad no longer recognized himself and the members of his family, the moment had come when you could no longer leave him alone. I woke up one night. There was a strange silence. I went looking for my father. He had lit the stove, but instead of the burner he had used the ash storage compartment. Everything was full of smoke.

It is very easy to make a person with dementia anxious, as they cannot follow causal links. They would get scared should a bowl fall from the table, as they are afraid of the noise which they can’t explain. When it was quiet at home, father was very peaceful, but the tiniest change or noise would make him anxious.

I couldn’t watch over my father all the time. I spoke with the ladies living next door, asking if someone could look after him. He had to be taken care of twenty-four hours a day, or else it’s trouble. The neighbors would often call, saying, Your father is walking around, come and get him. He was very adept at these silent escapes! One time he even used the window. I got him to go to bed on his own accord. After a little while it became terribly silent. I went looking for him, and he was nowhere to be found. He had left through the window, going away who knows where.

It was characteristic that he would be friendly towards women and gladly remain with them, but he acted suspicious towards men. As soon as a man entered the room, he started worrying and asking: “Who is this? What does he want with us?” My father had spent his working life as a radio mechanic at a Soviet airfield. Soviet soldiers often arrived, uninvited, to locals’ houses, demanding different goods. Maybe this is why he didn’t trust men he didn’t know. One time he escaped and I set out to collect him, and he got frightened of me, a man. He had picked up a stone and put it behind his back to protect himself. Well, I started talking with him, saying we’ve got to go home. I suppose he understood that I’m on his side. He let the stone fall down. He wasn’t really aggressive in his day-to-day life. I heard a woman living next doors becoming very aggressive, almost to the point of hitting others with whatever was at hand. But dad was quite the opposite. He was very, very quiet. If it was quiet at home it was alright. I don’t know. Maybe it’s different for someone who is used to spending their days in front of the TV. But he lived in complete silence.

It was interesting to see that people who didn’t know dad beforehand would wonder, Why did you tell us he was ill? He could talk about everything perfectly, still joking around. It seemed he was perfectly fine. A neighbor of ours had a daughter who would sometimes come visit. She had also been diagnosed with dementia. The two of them got together very well. You could leave them to sit, chat and talk together, like, This birch tree is swaying in the wind so gracefully! Nature is generally important for people with dementia. He could spend a lot of time looking at a birch tree swaying in the wind. He also had his wife’s dog beside him, which he could pet.

Up to the last moment, he collected firewood. This was important to him. “Is there enough firewood?” he would ask. He cut it himself and brought it inside. I didn’t even notice this, but the neighbors said that he wouldn’t stop even though the saw was broken. The saw was red with rust but he could still use it to cut firewood. Snowfall was welcome news, because that meant he would have something to do. He would shovel the snow, go inside to rest, and then go to shovel some more. As a person, he found it very important to constantly keep busy. I suppose that the sense that something should be done, without knowing what exactly, unnerved him from time to time. Some of the things he did in a most peculiar way. He had dug up perfectly good flowers from the flower-bed; cut branches off the trees. He had to keep busy. One time as he pulled something towards himself in the barn he hit his head and lost consciousness. He shaved regularly but would often cut himself and walk around bloodied without being aware of it.

Some young people had pilfered off of him, with things going missing from time to time. One time I caught them in the act. They asked me: “But where’s the old man?”

“What do you want with him?” I asked

“We need the No. 10 screw key. He usually gives something to us.”

It is likely that he gave away his stuff to many people. At some point I needed to cut something with a saw.

“Where’s the saw?” I asked him

“I don’t know.”

Well, there it was. That’s how it disappeared. Someone had probably asked to borrow it…

But his car was very important to him. It had to be there at all times. My son (his grandson) had come here at some point in time and I told him: “Well, why should it just stay here to no purpose. Take it!”

But this turned into a great ordeal for grandpa. For the next three days, he was walking around saying: “Someone stole my car! My car got stolen!” He kept on repeating this until it was returned to him. I tried explaining to him, saying: “Your grandson borrowed the car. He drove to Liepāja with it.”

“Did he? Alright.”

After a little while he again started pacing to and fro looking preoccupied. I asked him: “Well, what’s the matter?”

He didn’t fully trust me either. “I can’t tell you!”

“Really. What has happened?”

“Well, I… I can’t tell you!”

But I pressed him and finally he told me: “You see… my car got stolen!”

“No one stole your car,” I told him.

“But it is no longer there!”

The social support system when you are facing dementia is virtually non-existent. Even the so-called retirement homes don’t willingly accept people like him. When I inquired if they’d accept him, they asked me: “And is he really not aggressive?” “No, no!” I told them. They really didn’t want to take him in. One of the retirement homes told me straight away not to take him there. Thankfully they took him in at Pāvilosta. Even then, the neighbors from the village reprimanded me for taking my father to a retirement home.

“Well, there’s another possibility. How about I take him back and pay you €500 a month to help me take care of him?”

“Oh, no. Not for €500!” they said.

Still, after a little while they went on again: “Oh, no! But he’s all alone in there!”

“I’ll take him to you. I will pay you for watching him.”

“No, no, no…”

Thankfully he was not the aggressive type. I don’t even know what there is to be done if someone’s aggressive. It turned out alright, I think. One could scarcely have done anything better. But I didn’t know who I should have turned to for help. Psychiatric hospitals admit people like him for a month at most. If you cannot pay for a retirement home that can take them in, I don’t even know… You go to work one day and return to see your house has burned down, or maybe they have gone missing. My dad ran away from the hospital, too. He had almost made his way to Lithuania. Just a while longer and they wouldn’t have found him, zilch! I now read news about seniors leaving their home and going missing… But they don’t tell whether they have dementia or not.

There are no Latvian-language resources on dementia to be found. No one is also eager to inform others about it. Some descriptions would have been in order, at the very least. What things to do and how to do them. Even the doctor at the psychiatric medical center told me: “Oh, dementia. Well then, it’s clear now.”

“And what do you intend to do?”

“Well, we’ll work with him. But understand this – he will not improve. He will only become worse.”

But what about the future? What should one prepare for? What course of action should one take?

The mother-in-law

It was on September 1 that I took my mother-in-law to the psychiatrist. I was chuckling to myself: see, the children have finally finished school. It’s September 1 again, but now I am taking the old lady to the psychiatrist, and a new cycle is starting.

My mother-in-law had dementia, but seeing as we lived apart we didn’t notice any changes early on. We did catch on, upon going down to see her later, that she would repeat the same questions about the children each time. But for some reason we didn’t pay it much attention. We didn’t visit much as she lived in a different city.

Her husband was living with her. He was not the father of my husband; she married him when her son was already an adult. Our children nevertheless called him grandpa. Grandpa was the first to alert us about the situation. We started buying her vitamins and some such things, but grandpa still complained quite insistently that he couldn’t take it anymore. Things are not good, most definitely not! But we were busy with our own lives and didn’t pay sufficient attention. Of course, we helped them from a distance, as much as we could. After a while we realized it was getting worse and worse. Following the visit to the psychiatrist we really came to terms that things were very bad.

Both of our seniors lived in an apartment in Skrunda. He had had problems with alcohol but then he started getting it together, going on walks with grandma. He looked after her and kept us up-to-date over grandma’s condition. It was so bad, she had burned something while making soup, he would say. He gave us constant updates but still we wouldn’t really understand how bad it was. And then he couldn’t put up with it anymore and hanged himself.

We had a free week during our vacation and we took grandma so that he could get some rest. He said that he would like to take care of some health-related things. Apparently this was his choice: putting things in order and then leaving.

It hit us very hard. We then took her in and understood that things had gone fully, completely off the rails. It was very difficult. We realized we couldn’t leave her home alone. Before, when we went visiting, we caught on that the way she spoke was off, but we were confident that grandpa would look after her, thinking that he was more or less able to deal with it as he had gotten it together. Now we could see how it really felt.

In September six years will have passed since her death. We took care of her for the three final years of her life.

We found her a nurse very early on, seeing as we couldn’t leave her on her own, because she would always ask to be taken home. Grandpa had said, earlier, that he couldn’t bear her fashion of packing things and wanting to go somewhere. Even then she had told him that she wanted to go home. Grandpa had told her that she was home already. But she retorted: “No! I want to go home!” At the start, we couldn’t understand what on earth could she mean by this. What was home?

She had grown up in Liepāja, on the same street where we live now. She lived at No. 12 whereas now we live at No. 14. Her son, who is my husband, had grown up here, and that’s why we’re here. She started saying that she needs to go to Liepāja, to her mom’s, to go home. And she started packing her bags. Grandpa had told us about this, but now we saw it with our own eyes. She collected things, packed them in numerous bags and wanted to go home. “But you are already home, in Liepāja, on the very same street!” But she would still say: “No! I need to see mommy!”

Her mother had died rather young. Her grandson (my husband) was a teenager when his mother’s mother died of cancer. They were all of them living together, as the father of my mother-in-law had been deported to Siberia when she was only a one-year-old, and her mother never married again. Both of them kept living together and only when the mother of my mother-in-law died did she truly separate herself and get married. She had had partners, but she lived with her mother. She was in hiding throughout the war, also together with her mommy.

She had been a kind person, very well-disposed towards everyone. She never got angry. But as dementia set in she became furious. I got the impression that all the feelings she had repressed came out. She didn’t want to wash herself. When I took her to the shower she would hit me with her slipper and push me away. It was at this time that her aggression started showing itself. Earlier, she was never so. She was all but a saint! I had a perfect, very good mother-in-law who didn’t interfere with our lives and didn’t demand attention. My children too remember grandma as an exceedingly kind person. But this aggression came to the fore during her dementia. It was very hard to bear.

Thankfully we had the means to set up a separate room for her. After a year had passed, for example, we would sometimes wake up to see grandma in the corridor. We couldn’t even understand where she had found all the bundles and bags. As she didn’t allow us to cut her hair it grew very long, in three rows down to her waist. She would comb her hair and roll the ones that fell out into a ball, which she put inside her bundles. Long after she had left us, we would still find these balls of hair tucked away in nooks and crannies.

Another night, towards the morning, we found her in the hallway. She had already packed and was sitting in her nightgown. She had donned a boot of mine on one foot and a sneaker on the other. She had put on the first hat she had found. She was sitting in the hallway and pummeling away, asking to be let outside. My husband even installed a camera to keep tabs on what’s happening. We realized we couldn’t leave her alone, not even for a moment.

We found a very good nurse for grandma. A retired teacher, she would visit us each day. But she still regressed very quickly. We had taken grandma along to her husband’s funeral, but even there we recognized that she didn’t really catch on about what’s happening. At the beginning she could still recognize us but that didn’t last long.

For some time, when she could still read, we realized that it was good to leave big notices that she could read and which could calm her down. For example, “GRANDMA, IT’S ALRIGHT!” or “I’LL BE HOME SHORTLY”. Because she would also start shoving and pushing the nurse about, likewise treating her in an aggressive manner. But the notices we left helped her for some time.

We had to apply ourselves creatively, trying to come up with something that we could write to calm her down. For example, initially she was asking for her son all the time but then started calling him by her husband’s name. She then started calling me mother. It was then that we started coming up with notices like “I’LL BE HOME SOON. MOM.” Together with the nurse, we found that she would calm down briefly after reading these. This seemed like a very, very long time to us. It was very, very drawn-out.

Grandma never understood that there was something wrong with her perception. Before she became ill, my daughter did mention that grandma was only interested in telling her stories of the past and showing her old photos. Looking back, we realize now that maybe she did have an inkling of what was to come. We didn’t visit her that often. Nobody had the time. Like, see, we would come to visit later, in the summer most likely.

We weren’t there for her right from the outset of her dementia. When we started living together with her, she would sometimes lose all sense of reality, the what, the where… She lost her sense of taste. She could eat anything at all. We asked her: “Does this taste good? Or doesn’t it? What do you want to eat? Some soup, perhaps? Bread?” She could tell the difference between different foods, but she didn’t care. Sometimes it seemed that her sense of reality did come back. We walked around the neighborhood of her childhood, and sometimes she did know where to go, but then she didn’t and wanted to go home. I asked her: “But where should we go?” She could only say, “Home!” At some point we had had it, so we made a notice saying “YOUR HOME IS HERE”. She had a beautiful name. Saksija. We made notices for her: “SAKSIJA LIVES HERE.” “SAKSIJA’S HOME IS HERE”. But soon after she forgot her name, too. This concerns going home, too. Before living in central Liepāja, she had lived in the neighborhood called Jaunā Pasaule. Afterwards, she regressed further and wanted to go not to her home in the city center but the one in Jaunā Pasaule. As dementia patients regress, it all seems to turn topsy-turvy. While she was still living with us we could keep track of her delusions, but this ended when she moved to the retirement home.

Presence was very helpful in the beginning. When all of us were home, when we were present, we talked to her and it seemed to help her. The nurse was very good in that she accepted everything that was happening and talked to her a lot. The nurse had taken a great liking to our grandma. I later saw that she had left flowers at her grave. I do think that presence and talk are beneficial. In the retirement home she regressed very quickly. I, too, witnessed the way in which her three roommates, all of them old ladies, also regressed.

We had applied for a state retirement home but her turn came when she had already died. But we understood we could no longer hold grandma in check. At some point she almost blew up the house by turning a valve in the boiler room. Steam had started to escape from somewhere. Thankfully my husband was home, and the nurse could call him for help. We then put grandma into the hospital, as she wouldn’t sleep at night at all. The psychiatrist said that maybe she should be committed to a mental hospital. And we think that it precipitated her decline, and that it’s true what everyone says. At the madhouse, they tied her up and drugged her, of course. And then we got a spot in the retirement home. She spent about two years in isolation with three other old ladies just like her. They gave her calmatives there, too. She regressed even faster than before. She talked less and less. All of the old ladies were alike there and wouldn’t talk much to one another.

We went to visit once a week. We took her out. Of course, she would have needed more, but that was all we could do.

I recall a visit I made with my daughter about a year before grandma passed away. She no longer spoke. We went outside for a walk. She didn’t struggle anymore, absorbed as she was in her own little world. Me and my daughter were talking about this or that, and she was sitting beside us and smiling. She was there, but she also wasn’t. We heard a rooster cock-a-doodle-doing somewhere. We laughed a bit about this and I started singing Kur tu teci, gailīti [Where are You Going, Little Rooster?, a Latvian folk song - translator’s note]. My daughter joined me as she was also having fun. And then I saw grandma looking at my lips. And she started singing along! It was such an event, a veritable shock! Her gaze would usually drift about, but at that time she really looked at my lips and started singing along, one song after another, and she could sing all the “timbaka, taibaka tillidirā” correctly too! She first started humming along and then she could sing the words, too. It was such great progress! I became convinced about the efficacy of musical therapy and now I keep telling experts that music can be of great help. I thought to myself, Damn it, why weren’t we doing this earlier?! These children’s songs really can help, and this should be researched more. It is very interesting. It was positively shocking. I was in great spirits and kept telling this to everyone as if I had seen a miracle. She could remember the words when it seemed that all had been lost thanks to the music. We tried repeating this the next week, but it no longer worked. We realized it was too late.

The public have no knowledge about dementia, and the lack of information causes denial. Upon visiting grandpa we, too, told him that it wasn’t so bad. We didn’t believe him. When we took grandma in, we saw that it really was. Only then did we understand what had happened to grandpa. Because he didn’t keep silent. He talked and he called us. Of course, we listened to him and we brought them food, since he said he couldn’t leave grandma alone anymore. We were perplexed, though. How come you can’t leave a grownup person on her own? But of course we brought the products so that he didn’t have to go to the store. We helped, but the lack of understanding… But, you know, if you haven’t seen it, you can’t understand it. If I hadn’t lived through it, I wouldn’t have known what it entails and what you have to deal with. And what we don’t know doesn’t exist for us. And if you see someone half-mad on the street there is no understanding as to what’s happening. It is very difficult to understand it if you haven’t faced it. It is very difficult to understand.

© 2022

Anna Priedola