Like every year, an empty building in Riga was chosen as the venue of the festival, in order to draw attention to the potential of its future development. For SK 11, it was the former Museum of Literature and music, located on Terbatas street 75.

Tērbatas iela 75: From a fish canning factory to a repository of spiritual values

Text: Laura Briede

Construction first began at Tērbatas 75 at the turn of the 20th century. At that time, Riga was one of the most developed cities in the Russian Empire. The 1870s and 1880s saw the dawn of the “heavy industry era” in Riga, characterised by a rapid growth in manufacturing: new factories were being built in Russia at large and in the Baltic gubernias in particular.

The rapid industrial development in Riga during this period also fostered the circulation of money, which, in turn, gave rise to ideal circumstances for growth in construction. An important part of the city was rebuilt during this period: its historicist architecture, by then devoid of new ideas and exhausted by its own excesses, was replaced by buildings featuring the sinuous flora and fauna of a stylised art nouveau aesthetic, though practicality in city planning still reigned. This heritage has accorded Riga the title of the North European metropolis of art nouveau. Its industrial and art nouveau architecture are now seen as “different parts of the mosaic of an era”.

Taking a broader view of the industrial heritage of Riga from the end of the 19th to the beginning of the 20th century, one can only marvel at the results achieved in various sectors. The first Russian bicycles and automobiles were built at the Leutner & Co. and Russia factories, respectively. The first tank was created at the Russo-Balt rolling stock factory, where fighter planes were also built according to serial designs. One of the most well-known factories in Riga included the complex of the Russian electric company Union (later to become the State Electric-Technical Factory, known by its acronym VEF), which gained international popularity with its miniature Minox camera. Today it is rather difficult to imagine the scale at which the French-Russian rubber company Provodņik (Проводник) used to work: it was the largest rubber factory in Russia and, in terms of its total production, the fourth largest in the world. Beer brewing was also on the rise. Riga’s nine large breweries complemented the 110 located elsewhere in the territory of present-day Latvia. In addition to the above, there were a number of other gigantic production units. This rapid industrial development was abruptly halted by the First World War, during which factories and their workers were evacuated to the Russian mainland.

Next to several rental buildings designed by Konstantīns Pēkšēns, Eižens Laube, Jānis Alksnis, and Friedrich Scheffel, the steel factory Birman und Frank was commissioned by the industrialist and philanthropist Leon Birman (1863–1933) and constructed at Tērbatas 75, functioning at this address until the First World War. In the industrial construction of the era, eclectic architecture was still dominant, usually expressed in “brick style” façades without any plaster. To this day one can see vestiges of this style at Tērbatas 75; the plasticity of the brick style is evident in the treatment of window openings and cornices.

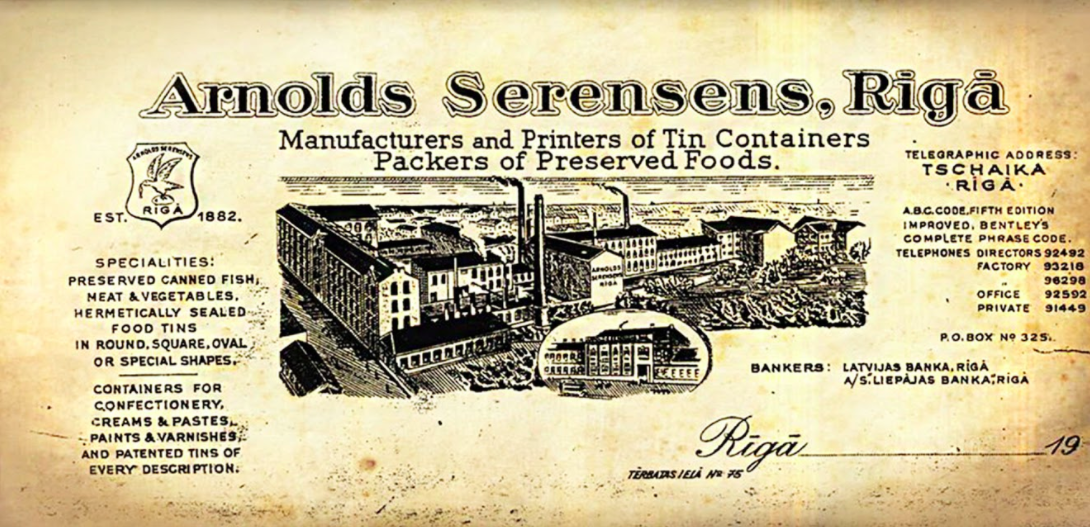

Seventeen years later, the premises were taken over by the canned and steel goods factory of Arnold Sörensen, which had been established 40 years prior in Tallinn and partially evacuated, during the First World War, to Russia. After the Second World War this company was replaced by Kaija, a group of canned fish enterprises, which functioned at this address for 64 years, later moving to new premises in Vecmīlgrāvis.

The newspaper Rīgas Balss reported in 1985: “The territory still belonging to the group of enterprises is littered with trash, windows have been broken, the power installation equipment and heating systems have been demolished. Several precious pieces of equipment have been disassembled and abandoned.” In an article published in the newspaper Literatūra un Māksla in 1986, Jānis Lejiņš mentions that, at the time, the factory complex was listed in the register of protected cultural monuments. Yet, it has not retained that status. The address is today no longer found in the updated list of industrial heritage sites compiled by the Department of National Cultural Heritage.

When, in 1986, the former inhabitants had readied the factory complex for transfer, some of the former Kaija buildings were given to the Latvian National Library (then the Vilis Lācis State Library) on the condition that it move about 300 000 units of its collection from four buildings in the Old Town to the new premises at Tērbatas 75. In time, major repairs were carried out on some of the buildings, yet the overall conditions were completely unsuited to the temporary preservation of the library collection: the premises were without heating, water or sanitary facilities. Subsequent developments were rather dramatic: mould spread through the books at lightning speed and an unsuccessful search for those responsible was conducted. In late 1990, an heir suddenly appeared and, without any documentary evidence, Riga Regional Court ordered part of the territory at Tērbatas iela 75 to be turned over to them. The National Library moved out in the second half of 2014, when the newly built Castle of Light was opened for it at Mūkusalas iela 3.

Parallel to the functioning of the library, in Block 3 of this complex Ilmārs Ēlerts (1948–1991) established an experimental youth theatre studio Apsēstā māja (“The Haunted House”), which offered a visual, form-based theatre performed by amateurs and professionals that incorporated the idea of “poor theatre” and departed rather sharply from the influence of state theatres. In the late 1980s, Ēlerts’s studio—along with other amateur groups such as the Riga Chamber Theatre, Kabata, the Riga Musical and Poetic Theatre, the Movement Theatre and the Costume Theatre—supplemented the traditional repertoire of the state theatres with a new type of informal stage performance.

In 2014, the collection of the Museum of Literature and Music—which, as the Rainis Literature and Art Museum, had occupied five rooms at Riga Castle since the 1970s—was moved to the premises. Like the library, the museum only remained at Tērbatas 75 for an interim period, until January 3, 2020, when it could begin moving to its new premises at Pulka iela 8, where it will have to patiently wait for space to be arranged for its permanent exhibition at Mārstaļu iela 6.

Across from what was then the main building of Kaija, the Riga Sports Palace was opened in 1970 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of Lenin. This iconic building, designed by Oļģerts Krauklis according to an All-Union matrix, was constructed on the site that in the late 1950s had been designated for the construction of a panorama cinema and concert hall, neither of which were ever built. Later, the Sports Palace was privatised and, in 2008, razed. In order to restore the degraded city block, the Estonian real estate developer Rotermann Group has plans to construct Rotermann Square on the site—a complex of entertainment facilities, offices, and apartments. In this context, it is worth noting another, already realised project by the Rotermann Group: the famous Rotermann Quarter in Tallinn, the value of which is augmented by the carefully preserved industrial heritage of the 19th-century Rotermann Factories. The restoration projects for the quarter were developed by leading Estonian architectural bureaus, adding contemporary architectonic highlights to the old industrial buildings.

The project on the block where the former Sports Palace once stood is yet to be carried out, but the developers, Rotermann Latvia, are planning to revitalise the area with a temporary project that has just received approval from the Riga City Building Authority: before construction begins on Rotermann Square, mobile urban gardens will be installed here, in response to the desire of the city’s residents to feel closer to nature and in order to provide them with the opportunity to grow their own fruits and vegetables. The pandemic made the need for time spent in nature particularly acute.

In time, as the Rotermann Square project is carried out, the empty space that used to be the Sports Palace quarter will be filled with new architectural content conforming to our current aesthetic assumptions and understandings. Yet the future of Tērbatas 75 is less clear. This address highlights a situation typical not just of Latvia but also elsewhere in Europe. The historical production units are no longer functional and have been replaced by new enterprises that produce much less than the gigantic volumes churned out by industries here in the past. There are many abandoned and degraded factory premises (including some built relatively recently) that either cannot be used for contemporary manufacturing or would require too many resources to be adapted, even for other purposes. Yet European cities are looking for opportunities to transform and revive factories for various new uses. Examples are to be found in Western Europe and Scandinavia, where adaptations of function and the revival of whole regions have been realised successfully while still preserving the historical evidence of industrialisation. Principles for the transformation of industrial objects have been applied similarly in Riga as in other European cities. Former industrial zones are now most often sites for offices and stores. Yet there are a number of interesting examples of industrial heritage in Riga that, though often unnoticed by passers-by, nonetheless contribute to the city’s identity. Gas Factory No. 2 on Vagonu iela is nowadays used by AS Latvijas Gāze, and its three natural gas reservoirs have been successfully restored and are used for purposes similar to those that were originally intended. The building of the Latvian National Opera and Ballet at Aspazijas bulvāris 19 is another example. At the end of the 19th century, the First Riga Electric Power Station was built between what is now the opera house and the city canal, and a part of it is still visible today. In 2001, when restoration and reconstruction work was done, the canal-facing façade of the power station and its chimney were preserved. Such nuances make the urban environment into a lively organism that is full of interesting stories.

Juris Dambis, Head of the National Cultural Heritage Department, mentions what may seem as a self-evident truism in his doctoral work in 2010: “As time passes, society’s attitude to cultural and historical values changes. In contemporary understanding, the notion of cultural heritage has expanded from individual architectural evidence to the protection of the historical centers of cities. That which a part of society used to consider ‘old dumps’ sometimes turns out to be something to value.” In order to evaluate and thus to preserve and develop a cultural treasure—in this case, that of industrial heritage, on which research only began to be carried out relatively recently, in the 1960s—an essential detail is necessary: authentic evidence of the era when it served its function.

In order to produce harmonious and high quality architecture when preserving sites of cultural heritage, it is important to take into account three important components: the physical size and form, the emotional attachment of the city’s residents, and the history and functions of the site. As far as Tērbatas iela 75 is concerned, it is impossible to highlight just one authentic nucleus of value in its history, which spans the times of Arnold Sörensen and Kaija, the temporary housing of the National Library and the Museum of Literature and Music, and the period of Ēlerts’s experimental theatre. Yet the juxtaposition of these functions and the historical uniqueness of the place radiate from every brick of the redesigned, rebuilt, and repaired complex and the affectations of dusty newspaper articles.

It is possible that events like Survival Kit—short-lived yet important—can once again draw attention to this historical heritage and contribute to discussions about the sustainable, people-friendly development of the city.

Literature

Antenišķe, A. Rīgas industriālais mantojums Eiropas kontekstā // Industriālais mantojums modernā pilsētvidē: starptautiska konference, Rīgā, 2002. gada 20. septembrī = Industrial heritage in the modern urban environment: International conference, Riga, 20 September 2002: Catalogue / Ed. A. Biedriņš. Riga: Rīgas dome, 2003.

Biedriņš, A. Latvijas industriālā mantojuma ceļvedis = Guide to industrial heritage of Latvia / A. Biedriņš, E. Liepiņš. Riga: Latvijas Industriālā mantojuma fonds, Valsts Kultūras pieminekļu aizsardzības inspekcija, 2002.

Celms, I. Teritorija jāsakopj savlaicīgi // Rīgas Balss, 1985. No. 91.

Cinis, A. Rīgas industriālais mantojums pilsētvidē // Industriālais mantojums modernā pilsētvidē: starptautiska konference, Rīgā, 2002. gada 20. septembrī = Industrial heritage in the modern urban environment: International conference, Riga, 20 September 2002: Catalogue/ Ed. A. Biedriņš. Riga: Rīgas dome, 2003.

Dambis, J. Rīgas centra arhitektoniski telpiskās vides kvalitāte, 1995–2010: promocijas darba kopsavilkums / Sci. adviser J. Briņķis. Riga: Rīgas Tehniskā universitāte, 2010.

Lejiņš, J. Gūtenberga kunga grūtdieņi // Literatūra un Māksla, 1986. No. 22.

Punga, I. Ilmārs Ēlerts vada pirmo patstāvīgo teātri Latvijā // Laiks, 1990. No. 2.

Rakstniecības un mūzikas muzejs uzsāk pārcelšanos uz jaunajām telpām // Latvijas Avīze, 2020. 3 Jan. Available: https://www.la.lv/foto-rakstniecibas-un-muzikas-muzejs-uzsak-parcelsanos-uz-jaunajam-telpam (seen 08.07.2020.).

Rīgas zivju konservu kombināts “Kaija”: dokumentinformācijas un literatūras rādītājs = Рижский рыбоконсервный комбинат “Кайя”: указатель документной информации и литературы / Ed. L. Rumba. Riga: Avots, 1988.

Zaļuma, K. Latvijas Nacionālās bibliotēkas ēkas simt gados (1919–2019) / Sci. ed. A. Vilks. Riga: Latvijas Nacionālā bibliotēka, 2019.